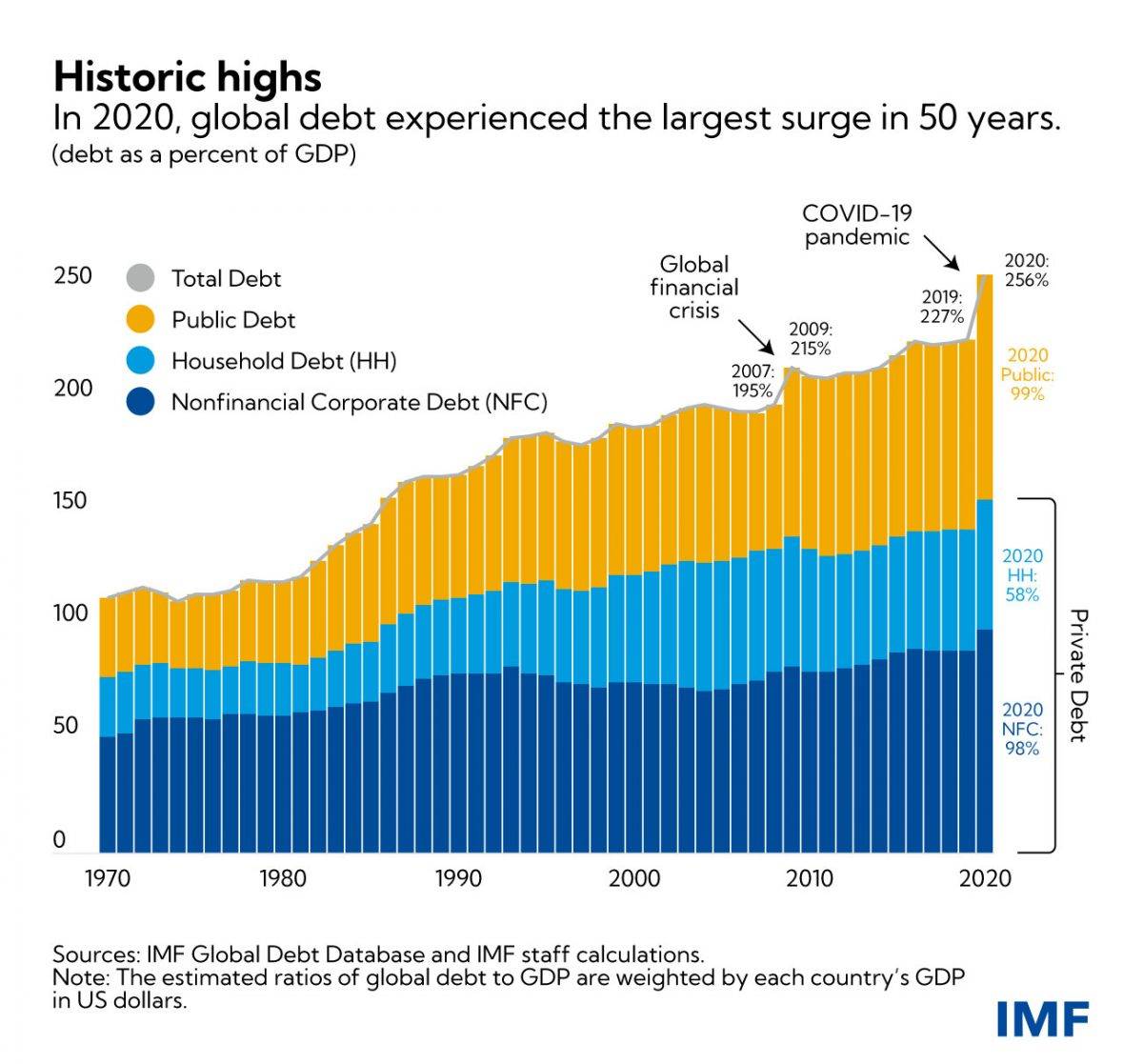

After being hit by a worldwide health crisis and a major recession in the first half of 2020, the globe experienced the highest one-year debt increase since World War II, with global debt reaching USD 226 trillion. Debt levels were already high prior to the crisis, but today governments must negotiate a world marked by record-high public and private debt levels, new viral mutations, and growing inflation, among other things.

According to the most recent edition of the International Monetary Fund’s Global Debt Database, global debt will have increased by 28 percentage points to 256 percent of GDP in 2020.

Government borrowing accounted for slightly more than half of the rise, with the global public debt ratio reaching an all-time high of 99 percent of GDP as a result of the increase. Additionally, private debt owed by non-financial firms and individuals hit new highs.

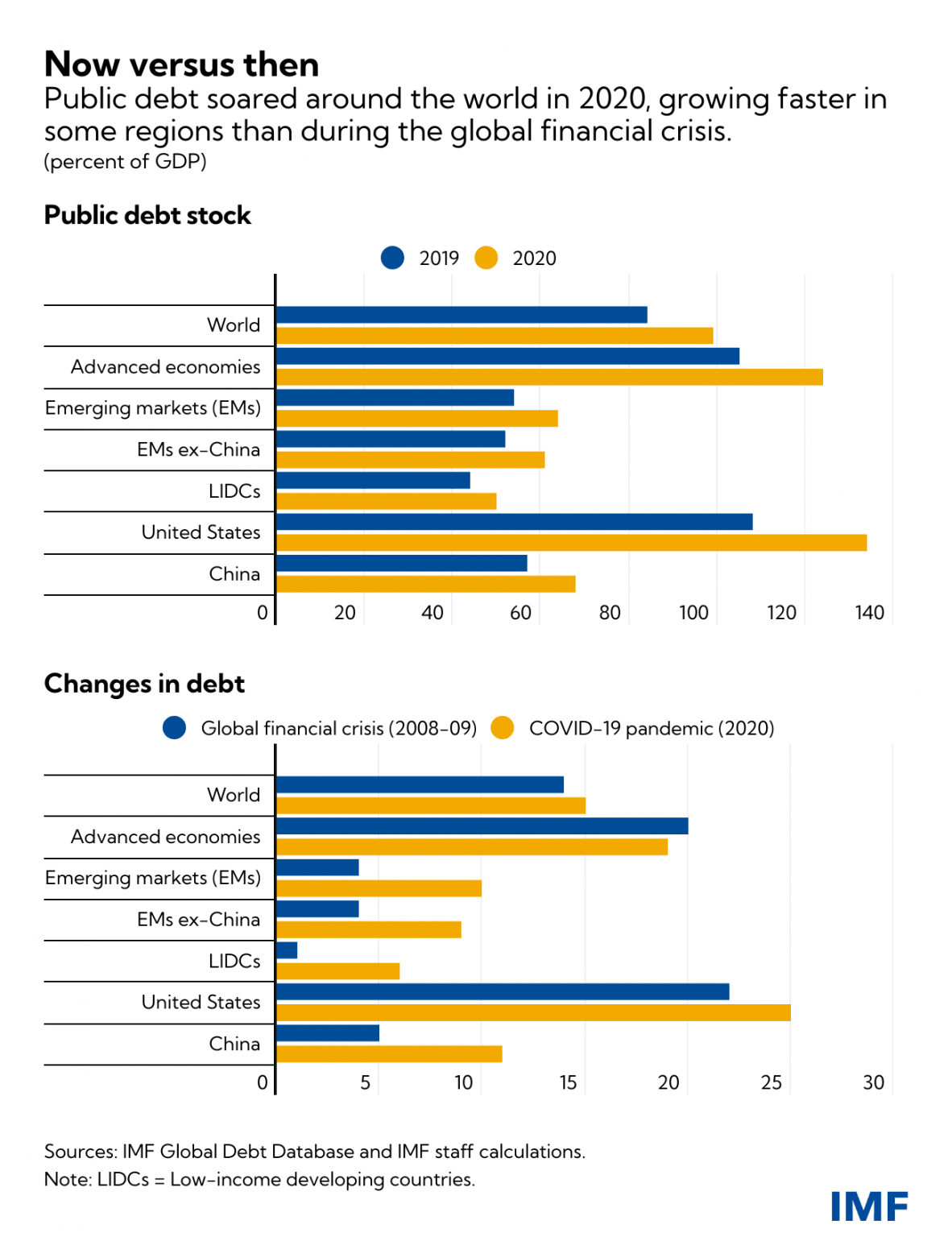

Deficit spending has increased dramatically in advanced nations, with public debt rising from roughly 70 percent of gross domestic product in 2007 to 124 percent of gross domestic product in 2020. On the other hand, private debt increased at a more modest rate, rising from 164 percent to 178 percent of GDP over the same period of time.

It is the greatest share of total global debt since the mid-1960s, with public debt accounting for about 40% of total global debt. Since 2007, governments have experienced two major economic crises, the first of which was the global financial crisis, and the second of which was the COVID-19 epidemic. The accumulation of public debt is largely related to these two crises.

The great financing divide

Debt dynamics, on the other hand, varies significantly from country to country. Advanced economies, including the United States and China, contributed for more than 90 percent of the USD 28 trillion debt increase in 2020. Because of low interest rates, the actions of central banks (including substantial purchases of government debt), and the existence of well-developed financial markets, these countries were able to increase both public and private debt during the pandemic. Most developing economies, on the other hand, are on the other side of the finance divide, with limited access to funding and frequently higher borrowing rates.

When we look at the big picture, we can observe two separate developments.

Advanced economies experienced record fiscal deficits as a result of the recession’s impact on revenues, prompting governments to enact extensive fiscal reforms as COVID-19 spread. In 2020, public debt will have increased by 19 percentage points of GDP, a similar amount to that experienced during the global financial crisis, which occurred over two years in 2008 and 2009. Despite this, private debt increased by 14 percentage points of GDP in 2020, nearly double the increase experienced during the global financial crisis, indicating the fundamentally different nature of the two crises. During the epidemic, governments and central banks encouraged the private sector to borrow more money in order to help protect lives and livelihoods from the disease. During the global financial crisis, on the other hand, the issue was to keep the harm caused by the excessively leveraged private sector under control.

Emerging markets and low-income developing countries had significantly tighter funding constraints, however there were significant regional differences.

China alone was responsible for 26% of the global debt rise. Emerging markets (excluding China) and low-income nations each contributed a tiny amount to the increase in global debt, roughly USD 1–1.2 trillion, owing primarily to increased governmental debt.

Nonetheless, both emerging markets and low-income nations face higher debt ratios as a result of the significant decline in nominal GDP expected in 2020.

In developing markets, public debt hit record levels, while in low-income countries, it reached levels not seen since the early 2000s, when many governments benefited from debt reduction programs.

Difficult balancing act

The significant increase in debt was justified to save lives, employment, and avoid a bankruptcy tsunami. The social and economic repercussions of inaction would have been severe.

But rising debt exacerbates flaws, especially as financing circumstances tighten. In most cases, high debt levels limit government support for recovery and private sector investment capability.

In a world of high debt and growing inflation, finding the correct blend of fiscal and monetary policy is critical. Fortunately, fiscal and monetary policy complimented each other during the pandemic. Central banks, particularly in wealthy nations, lowered interest rates, making it simpler for governments to borrow.

Inflation and inflation expectations are now the focus of monetary policy. Some debt ratios can be reduced by increasing inflation and nominal GDP, but this is unlikely to be sustained. Borrowing costs grow as central banks boost interest rates to combat excessive inflation. Many emerging markets have already raised policy rates and more are expected. The way central banks discontinue their huge purchases of government debt and other assets in industrialized economies will impact the economic recovery and fiscal policy.

Rising interest rates will necessitate fiscal policy adjustments, especially in debt-prone countries. Historically, increased expenditure (or lower taxation) had less impact on economic growth and employment, and could fuel inflation pressures. Sustaining debt is a major challenge right now.

Global interest rates rising quicker than projected and economy slowing are hazards. Stress on the most indebted governments, people, and companies would increase with considerable financial tightening. Growth prospects will suffer if the public and private sectors deleverage simultaneously.

For now, however, it is vital to strike a balance between policy flexibility, adaptability and adherence to credible and sustainable medium-term fiscal goals. This technique would reduce debt vulnerabilities and help central banks control inflation.

Targeted financial assistance will help protect the disadvantaged (see the October 2021 Fiscal Monitor).

Some countries, particularly those with significant gross financing needs (rollover risks) or exchange rate volatility, may need to adjust quickly to maintain market confidence and avoid further fiscal difficulties. Concerns about the epidemic and the global financial divide necessitate significant international cooperation and support for emerging.