Eve Hayes de Kalaf, Research Associate, CLACS University of London, and School of Language, Literature, Music and Visual Culture, University of Aberdeen.

_______

The globe has grown increasingly interconnected on a scale we never believed conceivable. Digital identity has been accepted by governments, banks, communications, transportation, technology, and international development groups. The current debate centers on the importance of accelerating registrations in order to ensure that every person on the earth gets their own digital ID.

We did not unintentionally enter this new era of digital data management. International agencies such as the World Bank and the United Nations have actively urged states to offer proof of citizenship to individuals in order to combat structural poverty, statelessness, and social exclusion.

To accomplish this, social policy has purposefully targeted poor and vulnerable communities – especially indigenous and Afro-descendant people and women – in order to ensure they receive an ID card for welfare payments. By trying to incorporate excluded communities, they are addressing groups who have historically been subjected to systematic exclusion and denied formal citizenship.

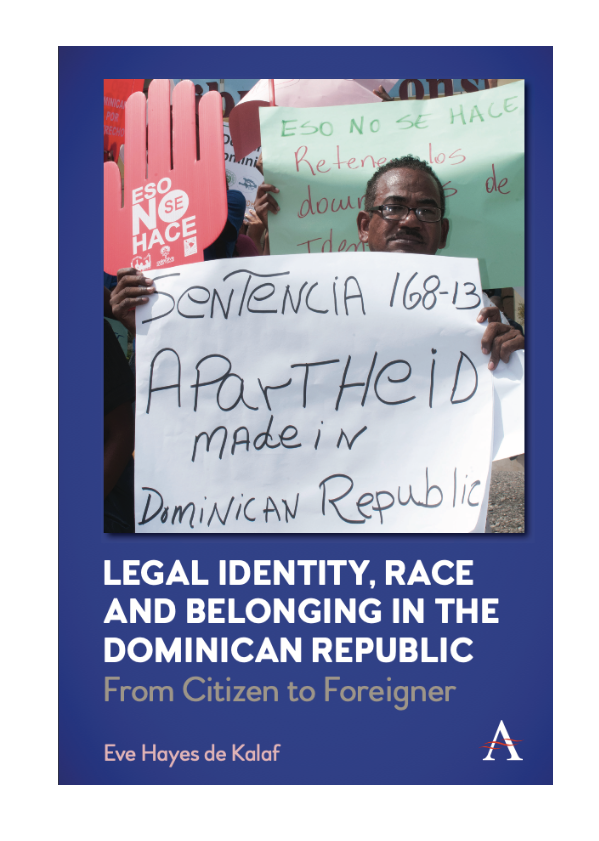

My research uncovered ways in which states might weaponize globally funded identification systems. The book that resulted from this work – Legal Identity, Race, and Belonging in the Dominican Republic: From Citizen to Foreigner – demonstrates how, in parallel to World Bank programs providing proof of legal existence for citizens, the government implemented exclusionary mechanisms that routinely prevented black Haitian-descended populations from accessing and renewing their Dominican citizenship.

For years, people of Haitian descent born in the Dominican Republic have been fighting a losing battle to seek (re)identification. Officials said that for over 80 years, they had incorrectly issued Dominican documentation to children born to Haitian migrants and now wanted to repair the error. These individuals claim to be Dominicans. They even have the documentation to back it up. However, the state disagrees.

These abuses resulted in a landmark 2013 judgement that deprived Haitian-born Dominicans of their Dominican nationality, thereby rendering them stateless. In response, a counter-offensive campaign demanded that the civil registry furnish all Dominicans of Haitian ancestry with their state-issued identification credentials as Dominicans.

My research reveals how foreign organizations at the time „looked the other way“ while the state began screening out and then purposefully barring Haitian-descended persons from getting their paperwork.

Who was declared eligible for inclusion in the civil registry (that is, Dominican citizens) and who was deemed ineligible as foreigners (that is, Haitians) was deemed a sovereign problem for the state to address. As a result, tens of thousands of people became undocumented and were consequently denied access to critical healthcare, welfare, and education.

Resolving the global identity crisis

Similar instances of this type of exclusion are sprouting in other parts of the world. I arranged a conference titled (Re)Imagining Belonging in Latin America and Beyond: Access to Citizenship, Digital Identity, and Rights at the University of London in June 2021. The seminar examined the linkages between identity and belonging, digital ID and citizenship rights, in conjunction with the Netherlands-based Institute on Statelessness and Inclusion.

It featured a paper on the French citizens affected by BUMIDOM, dubbed France’s Windrush. Additionally, we heard about legal challenges raised by non-binary people in Peru, the lives of stateless non-domiciled Cubans, and the “anchor babies” controversy over whether children born to undocumented migrants should be automatically granted US citizenship.

The program concluded with an international roundtable discussion on the discriminatory usage of digital ID registrations in other regions of the world. This includes conversations concerning India’s Assam people, Myanmar’s Rohingya, and Somalis in Kenya.

These types of debates will only become more prevalent over the next decade: a homeless man who is unable to travel on public transportation because the bus company only accepts card payments, not cash; an elderly African American woman who is unable to vote because she lacks a federally issued photo identification; or a woman who is told she must stop working because the system has flagged her as a „illegal“ immigrant.

For those who are excluded from the new digital era, daily existence is not just tough, but nearly impossible.

And, while the necessity to expedite digital ID registrations is critical, we must take a step back and reflect in this post-pandemic era. Demands for digital COVID passports, biometric ID cards, and data-sharing track-and-trace systems are facilitating the policing of not only those crossing borders, but also of communities living within them.

It is past time for a serious examination of the potential dangers associated with digital ID systems and their far-reaching, life-altering implications.

The Conversation has republished this article under a Creative Commons license. Continue reading the original story.

Discover other information: – Why NFTs Aren’t Just for Art and Collectibles

– How Microsoft’s Bitcoin Identity Service Gives You Control

– Bitcoin’s Non-Monetary Use Cases: Virtual Power Plants and Digital Identities – ‚Do Not Be Fooled‘ as the European Commission Considers a Crypto KYC Trap

– While the US Digital Asset Bill is ‚very measured,‘ it raises civil rights concerns – Attorney – Taproot, CoinSwap, Mercury Wallet, and the State of Bitcoin Privacy in 2021