____

Within their Carbis Bay communique, the G7 announced their intention to work together to handle ransomware groups. Days later, US president Joe Biden met with Russian president Vladimir Putin, where an extradition process to attract Russian cybercriminals to justice in the US was discussed. Putin reportedly agreed in principle, but insisted that extradition be mutual. But if it is, who just should extradited — and what to do?

The problem for law enforcement is that ransomware — a form of malware used to steal associations‘ information and hold it to ransom — is a really slippery fish. Not only is it a blended crime, including different crimes across different bodies of law, but it’s also a crime which straddles the remit of various policing agencies and, in many cases, states. And there is no 1 key offender. Ransomware attacks demand a distributed network of different cybercriminals, frequently unknown to each other to reduce the risk of arrest.

So it’s important to look at these strikes in detail to understand how the US and the G7 might go about handling the increasing quantity of ransomware strikes we’ve seen throughout the pandemic, with at least 128 publicly disclosed incidents taking place globally in May 2021.

What we discover when we connect the dots is an expert business much removed from the organized crime playbook, which seemingly takes its inspiration straight from the pages of a company studies manual.

The ransomware market is responsible for a massive amount of disturbance in the present world. Not only do all these strikes have a crippling economic effect, costing billions of dollars in damage, but also the stolen information obtained by attackers will still continue to cascade down during the offense chain and fuel other cybercrimes.

Ransomware strikes will also be changing. The criminal industry’s business model has shifted towards providing ransomware as a service. This implies operators provide the malicious software, handle the extortion and payment systems and handle the reputation of the“brand“. But to lower their vulnerability to the probability of arrest, they recruit affiliates on generous commissions to use their software to launch strikes.

This has caused a broad distribution of criminal labor, where the people who have the malware aren’t necessarily exactly the same as those who plan or execute ransomware strikes. To complicate things further, the two are assisted in committing their crimes by services offered by the broader cybercrime ecosystem.

How can ransomware attacks operate?

There are lots of phases to a ransomware attack, which I have teased out after analysing over 4,000 strikes from between 2012 and 2021.

First, there is the reconnaissance, where criminals identify possible victims and access points to their own networks. This can be followed closely by a hacker getting“initial access“, using log-in credentials bought on the dark web or obtained through deception.

Once initial access is gained, attackers want to escalate their access privileges, allowing them to look for key organizational information which will cause the victim the maximum pain when stolen and held to ransom. That is the reason why hospital medical records and police records are frequently the target of ransomware strikes. This key data is then extracted and saved by criminals — all before any ransomware is set up and activated.

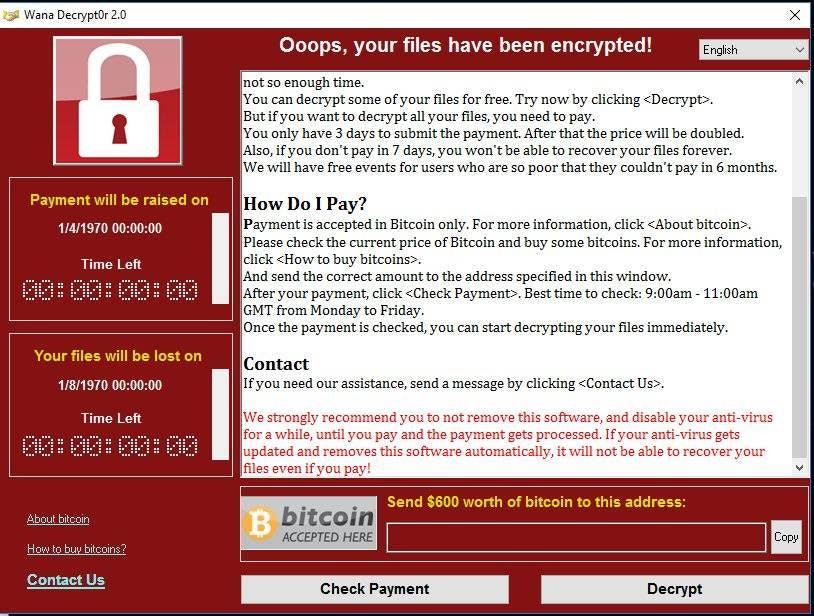

Next comes the victim organization’s very first sign that they have been assaulted: the ransomware is set up, locking organizations from their key data. The victim is fast named and shamed via the ransomware gang’s leak website, located on the dark web. That“press release“ can also include dangers to discuss stolen sensitive information, with the goal of frightening the victim into paying the ransom demand.

Successful ransomware strikes see the ransom paid in cryptocurrency, which is difficult to trace, and converted and invisibly to fiat currency. Cybercriminals frequently invest the profits to enhance their capabilities — and to cover affiliates — so that they don’t get caught.

The cybercrime ecosystem

As soon as it’s feasible that a suitably skilled offender could perform each of the functions, it’s highly improbable. To reduce the probability of being caught, offender groups tend to develop and master specialist skills for various phases of an attack. These groups benefit from this inter-dependency, as it offsets criminal liability at every stage.

And there are lots of specialisations in the cybercrime underworld. You will find spammers, who hire out spamware-as-a-service software that phishers, scammers, and fraudsters use to steal people’s credentials, and databrokers who trade these stolen information on the dark web.

They might be purchased by“initial access agents“, who focus in gaining initial accessibility to computer systems before selling on those access details to prospective ransomware attackers. These attackers frequently engage with crimeware-as-a-service agents, who hire out ransomware-as-a-service software as well as other malicious malware.

To coordinate these groups, darkmarketeers deliver online markets where criminals can openly sell or trade services, usually via the Tor network on the dark web. Monetisers are there to launder cryptocurrency and turn it into fiat currency, while negotiators, symbolizing both victim and offender, are hired to repay the ransom amount.

This ecosystem is constantly evolving. By way of example, a recent development has been the development of the“ransomware consultant“, who collects a fee for advising inmates at key phases of an attack.

Arresting offenders

Governments and law enforcement agencies seem to be ramping up their efforts to handle ransomware offenders, after a year blighted with their continuing attacks. As the G7 met in Cornwall in June 2021, Ukrainian and South Korean police forces coordinated to detain elements of the infamous CL0P ransomware gang. In precisely the same week, Russian federal Oleg Koshkin was convicted by a US court for running a malware encryption service which criminal groups use to perform cyberattacks without being detected by anti virus solutions.

While these improvements are promising, ransomware strikes are a intricate crime involving a distributed network of criminals. As the criminals have honed their methods, law enforcers and cybersecurity experts have attempted to maintain pace. Nevertheless, the relative inflexibility of policing structures, and the lack of a key offender (Mr or Mrs Big) to detain, may keep them one step behind the cybercriminals — even when an extradition treaty is struck between the united states and Russia. ![]()