Once upon a time, it was predicted that the internet would enable anyone with 1,000 admirers to earn a living, but Li Jin believes that in the age of NFTs, one or two devoted supporters may be sufficient.

Jin is a proponent of what she refers to as the „passion economy,“ an economic system that enables and encourages people to earn money while pursuing their passions. According to Jin, NFTs are a new tool that enables producers in the passion economy to connect with their „real fans“ and build enduring relationships.

Jin invests in “platforms that remove barriers to entrepreneurship and extend opportunities for work” through her venture firm, Atelier. With a background in venture capital, she is uniquely qualified to contribute to the transformation of how we think about employment.

Restoring the passion

“It’s always been a dream of mine to live in Paris, so I’m just hanging out here for the time being,” Jin tells Magazine at the close of the interview, which follows the conclusion of the city’s highly anticipated Ethereum Community Conference, or EthCC. Despite her admission that she does not „quite understand why people are working on DeFi,“ which captured the majority of conference attendees‘ attention, Jin „arranged a lunch for folks working at the junction of crypto and the creator economy.“

While the current difficulties of travel provide an excellent reason to savor every aspect of a new city, hanging out in a new place is not something the average worker can do “for the time being,” given their reliance on pesky things like physical offices and scheduled, mandatory in-person meetings. That is not the case for the majority of creators, particularly those in the passion economy.

After all, why do we work? When a youngster is asked what they want to do when they grow up, the response is frequently — and hopefully — lively and passionate. When people are asked why they picked a particular vocation, the answer is rarely about money, job security, or benefits. As they mature, many appear to reject these fundamental goals, opting instead to earn a living by conforming to corporate structures or mechanically fulfilling freelancing assignments.

According to Jin, the passion appears to be reviving. There is a “shift occurring from gig marketplaces, which were created around highly commoditized services and products, to more flexible, creative marketplaces that would enable individuals to earn money doing more of the things they truly enjoy,” she optimistically argues.

This is the essence of the love economy, which „represents a new kind of labor that is entirely distinct from the usual employer-employee relationship.“ This means that a passion „worker,“ if we can call them that, does not report to a boss in a corporate structure and does not operate as interchangeable — or fungible — freelancers on sites like Fiverr or Uber. Rather than that, they simply go about their business — and clients/subscribers pay for the luxury of being a part of it.

In certain ways, any creative worker’s output — whether written, designed, or painted — is a nonreplicable, nonfungible „token“ of their effort. This piece is, in effect, an off-blockchain NFT that I developed and sold to Magazine, but which will remain permanently connected to me. The labor output of non-creative workers like as security guards or Uber drivers is significantly less akin to a unique NFT and more akin to a commoditized, non-supply-limited „work hour“ token with a clearly defined market value.

The tie between NFTs and creative work transcends associative wordplay, since the technology enables creators to mint their work on the blockchain and profit from its sales and resales.

“This year, a lot of creators became aware of crypto and what it could do for them in terms of earning income in a way that wasn’t possible before.”

Entrepreneur

Jin was born in Beijing and moved to Pittsburgh in the early 1990s with her academic-minded parents. She remembers her early years in America as being „extremely destitute,“ prompting her parents to push her toward a safe job.

She enrolled at Harvard University in 2008, but her parents were dissatisfied with her major — English literature, warning her she was condemned to be a penniless writer and that her choice „was bringing dishonor to the family.“ Jin shifted her focus to statistics in order to pacify her parents.

She began her career as a reporter for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, where she was „assigned as a 19-year-old to cover the G20 meeting.“ She interned in mergers and acquisitions at Blackstone in 2011 and later worked as a strategy associate at Capital One and as a product manager at Shopkick, a Silicon Valley-based mobile shopping firm.

When Shopkick was bought, Jin „was unsure of my next role in technology,“ so she followed her classmates‘ lead and enrolled at Wharton in 2016 for a Master of Business Administration degree, but continued to apply for jobs. “If you want to stay in technology, you should consider venture capital – it will give you a bird’s-eye view of the entire industry,” a mentor recommended.

She withdrew two weeks into the program after receiving an offer from Andressen Horowitz, the renowned venture capital group dubbed a16z. “I wasn’t particularly interested in going to business school,” she recalls.

Jin’s responsibilities as a transaction partner included „meeting with startups all day, speaking with founders, accepting pitches, and assisting with the due diligence process,“ as well as frequently serving on the boards of directors of companies as an observer for her employer. Numerous these businesses are what Jin refers to as „consumer creative platforms,“ such as Imgur, Patreon, and Substack.

According to Jin, these enterprises represent a “shift away from the gig economy toward the passion economy, where new platforms empower people to earn a job doing what they love and monetize their uniqueness.” The tools necessary for a healthy creative middle class are being unleashed one by one. In her February 2020 post „100 True Fans,“ she puts forth a method for creatives to earn a $100,000 per year in the middle class with only 100 true fans contributing an average of $83 per month.

Today, a sizable portion of Jin’s envisioned „middle class“ of creatives remain digital peasants, „uploading, possibly, millions — hundreds of millions — of photographs daily on Instagram without receiving a cut of the advertising revenue.“

“Instagram earns a lot of money from advertising, but creators see none of it — I view this as 100 percent taxation.”

Artists receive no monetary compensation regardless of how many people read their profiles. On the other hand, Instagram derives „billions of dollars in equity value“ from the labor of its users – why shouldn’t content creators seek a cut of the cheese? Beeple exhibited approximately 5,000 works of art before cashing in on the NFT boom for tens of millions.

In July 2020, Jin decided it was time to put her words into action and „create an entire firm dedicated to this burgeoning category, which is what I did — and I also believed that the best way to understand and evaluate anything is to experience it.“

As a result, Atelier was founded as an investment firm with a $13 million initial portfolio of platforms that enable users to create their own futures.

“I started Atelier to fund a specific vision of the world: a world in which people are able to do what they love for a living and to have a more fulfilling and purposeful life.”

Cryptocurrency connection

Jin first became acquainted with bitcoin in 2017 when her business, a16z, became „one of the first funds to launch its own cryptocurrency fund.“ Though she frequently interacted with fund personnel, she found the industry abstract, since “it had not yet reached daily consumers.”

This year, however, things have shifted.

“There’s been way more intersection with consumers and the creator economy, particularly this year with NFTs.“

NFTs, Jin believes, expand on her concept of 100 true fans. “You may have just one true fan or, in an ideal world, two true fans bidding against one another,” she continues. Though just one individual would ultimately own each digital asset, „their work can remain publicly accessible and spread virally,“ triggering a chain reaction that increases the likelihood that true fans „who truly value and are prepared to pay for the original version“ will come along.

Jin auctioned an NFT symbolizing the paper titled „The Case For Universal Creative Income“ for 5.6969 ETH in April, with the proceeds going to Yield Guild Games‘ Sponsor-A-Scholar program. Though everyone can view the post for free, the original was purchased for 5.6969 ETH.

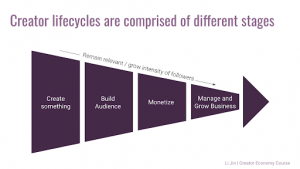

Jin believes that creatives should consider cryptocurrency as a means of monetizing their work, which she refers to as the third stage of the creative economy funnel. The first step is all about „How am I going to grow my following – how am I going to be discovered?“ The second step is „How can I deepen my audience engagement?“

While bitcoin and NFTs have enormous promise as rocket fuel for the passion economy, as Jin coined the term, her primary focus is on assisting creators in making the leap. She conducts a three-week course called „Building for the Creator Economy“ in which participants learn the ins and outs of her universe.

She also developed the Atelier Angels Pilot Program earlier this year, which will train 30 creators to become angel investors, allowing them to generate new revenue streams while also learning more about business. According to Jin and Atelier, the future belongs to the creators — and who better to invest in it than the artists themselves?